CAMILLE CHABROL

Portrait courtesy of Camille Chabrol.

Yale University M.Arch I 2020

Camille is a recent M.Arch graduate from the Yale School of Architecture. She completed her Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Philosophy at McGill University, and has worked in New York City; Montreal, Canada; Cairo, Egypt, and Brussels, Belgium. She is currently spending a year completing a research fellowship at the University of Cambridge. At Cambridge, she is researching the relationship between domestic labor, neighborhood networks in cities, and urban food systems. She is excited about the potential of incorporating this research into the design and planning of housing.

Co-Learning

What inspired you to pursue architecture?

Well, I’ve always loved cities and been obsessed with understanding how the spaces and environments that humans build –the ‘built environment’ – affects daily life, especially at the scale of the neighborhood. I became particularly aware of how urban environments and public spaces interact with social movements and politics when I was in Cairo during the 2011 revolution and in Montreal during the 2012 student movement. My initial interest in architecture therefore came from urbanism. As I learned more about the built environment, I became increasingly attentive to the role of aesthetics, form, and materials play in everyday life.

Building Project Pavilion, Addition, Exhibit Design, and Programming – With Deo Deiparine Exhibit showcasing the work of local organizations that are working on issues of homelessness and housing in Connecticut. Photo courtesy of Camille Chabrol.

What is the most important thing that you learned in the past year?

I would say the importance of working collaboratively and across disciplines, rather than individually on projects. This is a trend we’re starting to see emerge in architectural culture and education, which, till now, has largely emphasized individualism.

This past year I’ve had the opportunity to work with wonderful, talented, open-minded friends and peers. Everyone brought unique perspectives and styles, which resulted in stronger projects. The process of developing these projects was very fun and I think that in any collaboration everyone involved learns from one-another. COVID-19 has, of course, placed challenges on working together, but at the same time it has opened possibilities for collaboration across distances and time zones.

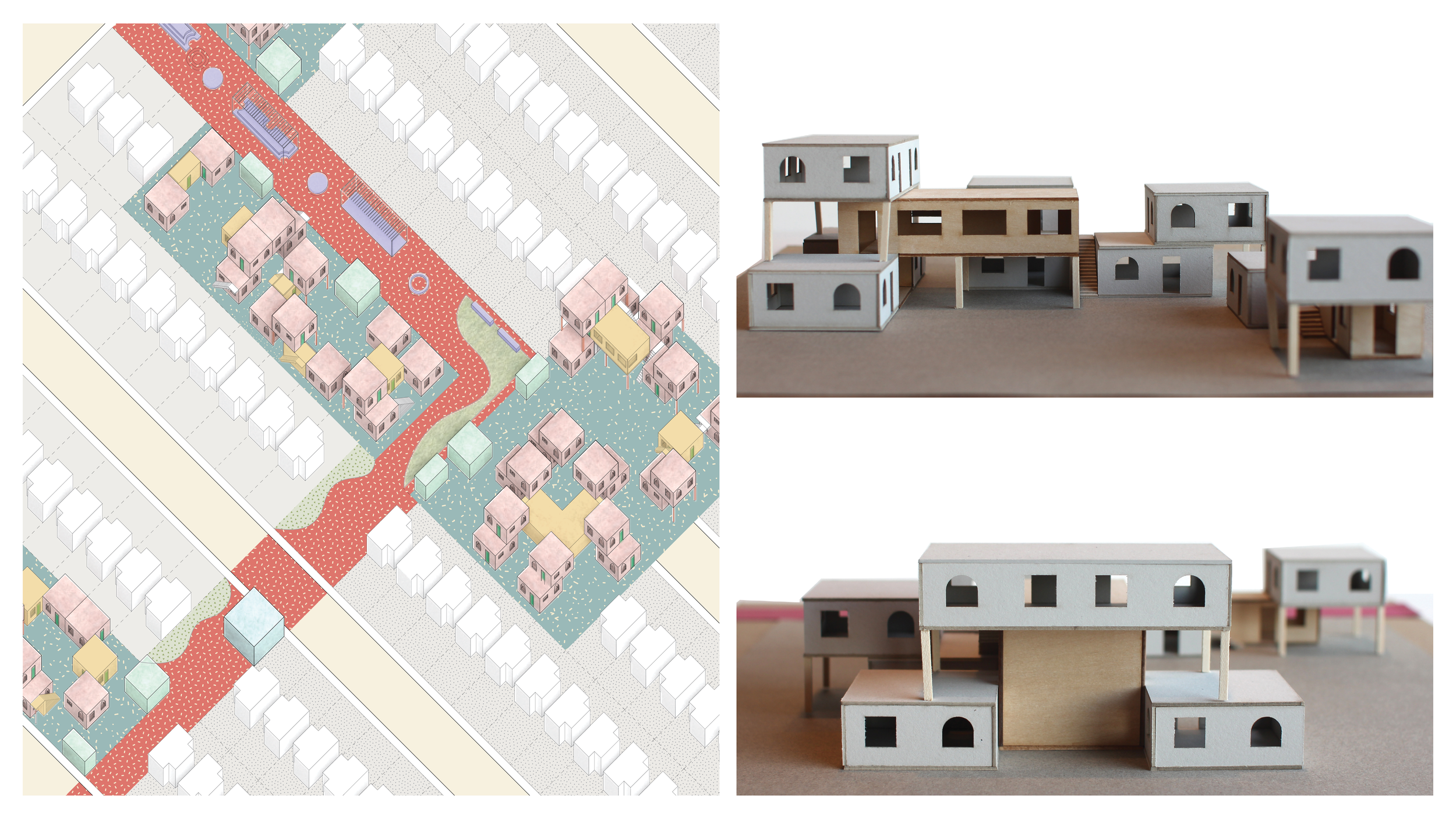

Proposal for Collective Housing Prototype – With Michelle Badr. Photo courtesy of Camille Chabrol.

What are some architectural organizations (or specific person/role model) that helped you learn to overcome an obstacle? How did they?

During this past year, two wonderful professors have transformed my perspective on architecture: Fernanda Canales and Ana Maria Duran Calisto. Both women are amazing role models who have the knowledge and confidence to address complex social issues from architectural and urbanistic perspectives.

Fernanda Canales was my studio professor at a time where I was doubting the ability of the architecture and design professions to make a difference in creating a more just, equitable built environment. From Fernanda, I learned how to work simultaneously across multiple scales, showing how the design of a single bedroom can affect the design of an entire neighborhood or an entire city, and vice versa. The details on a small scale can shape and even improve the quality of environments on a larger scale.

Then there’s Ana Maria Duran, who, through the example of urbanization in Amazonia, taught me to question widespread assumptions about the relationship between cities and nature. She also taught me about the intricate link between environmental justice and social justice. In this sense, I have learned from her the need to question the fundamental bases of urbanism, such as the false binary between nature and culture, urban and rural. The notion of “territorial urbanism,” urbanism in which natural and built systems are understood as mutually affecting one another, offers a possibility for rethinking cities in the context of the climate crisis.

City of Kitchens. A proposal for repurposing abandoned housing lots in the Angeles de Puebla development in Mexicali, Baja California. Photo courtesy of Camille Chabrol.

City of Kitchens. Photo courtesy of Camille Chabrol.

If you were given the opportunity to repeat the year, what is one thing you’d do differently?

This is a difficult question! Perhaps one important mistake that I have made in the past is to let work take up all my time. I think that in order to do meaningful work in architecture, it is important to pay attention to what is happening in the world and stay connected to your life outside of architecture. Of course, architectural work demands a lot of time and concentration, but if you are constantly in studio or at work and not participating in other activities, there is a danger of becoming disconnected, which is not good for you or for the architectural work you are making. I think that creating architecture in a silo is never a good thing.

City of Kitchens. Photo courtesy of Camille Chabrol.

As you reflect on the past year, what did you discover as your biggest strengths?

For the first two years of graduate school, I struggled with self-doubt and worried constantly that the work I was doing and the ideas I was contributing were below what was expected of me. I mention this because I think many young people, and especially young women, in architecture struggle with this. This past year I learned that rather than focusing on imperfections, what really counts is putting forward ideas that will lead to conversations. That it is important to be vulnerable by sharing your thoughts, doubts, and questions. Ideas develop best when they are challenged or supported by the people around you. At the same time, it is important to create space for, and really listen to the thoughts, doubts, and perspectives of others. So perhaps the strength I learned this year is the strength of vulnerability.

Beds&Beds—With Alex Pineda and Thomas Mahon. A proposal to integrate high-density collective housing with food processes and production. Photo courtesy of Camille Chabrol.

Beds&Beds—With Alex Pineda and Thomas Mahon. Photo courtesy of Camille Chabrol.

In terms of rising concerns and problems (in the architectural profession) over the past year, what is one change that you wished would happen and it did not? This can be in an educational or work atmosphere.

This year has brought to the forefront the ways in which whiteness and patriarchy are so deeply embedded into the functioning of the architectural profession, architecture culture and education. I am disappointed in how the will to address these issues has turned out to be superficial for many architectural establishments. I have noticed how for many firms and institutions, the philanthropic proposal to donate money to causes has supplanted the need to do genuine work of structural change.

Beds&Beds—With Alex Pineda and Thomas Mahon. Photo courtesy of Camille Chabrol.

Beds&Beds—With Alex Pineda and Thomas Mahon. Photo courtesy of Camille Chabrol.