IMANI DIXON

Photography by Kai Brown. Portrait courtesy of Imani Dixon.

Architect at Muller2

Originally from Springfield, Ohio, Imani Dixon, AIA, NOMA, is a recently licensed architect who currently works on transportation project types reaching thousands of people in the Chicago area. Prior to moving to Chicago, she received a Bachelor of Science in Architecture from Bowling Green State University and a Master of Architecture from the University of Cincinnati. Since graduating, she has been involved with mentorship programs and pro bono projects through ACE Chicago and I-NOMA and is the current Secretary for the Illinois chapter of NOMA. As one of the approximately 500 (and growing) Black women licensed architects in the country, she has a passion for expanding the field of architecture for everyone, especially those from underrepresented communities.

Paying it Forward through NOMA, Mentorship, and Design.

What is your favorite dish?

Chicken Tikka Masala. It’s become my favorite dish in the past few years but because of the pandemic, I haven’t been able to go to my favorite Indian restaurant in a long time since I live pretty far from it. There’s a great place here in Chicago called Cumin in Wicker Park but the best I’ve EVER had was from Adeep India that I used to get all the time as a graduate student at Cincinnati.

What is your favorite song by a Black artist?

That’s difficult to pinpoint, but if I have to choose, I will go with the first song that I remember hearing, ever, by one of my favorite rap groups: “Award Tour” by A Tribe Called Quest. I have fond memories of my parents playing that song and it gives me a nostalgic feel; the song never gets old.

Three additional facts about Imani:

I played the trumpet for 7 years

I was Prom Queen in high school

I have 10 siblings!

What inspired you to study architecture?

My upbringing certainly influenced my interest in design in general. I spent a lot of time with my dad growing up who has always been a creative person. He would draw comic-like cartoons, create model planes, and build all kinds of Lego creations with me. I mirrored many of those creative parts about him that I was drawn to. As a child, I was very content with drawing some kind of meticulous art, like geometric patterns, by myself. I initially thought I would get into something like graphic design, but one of my best friends in middle school said she wanted to be an architect. At the time, I had a fairly limited definition of an architect, but since I was good enough at drawing and math, I knew it would be the right path for me, especially since I had always been more of an “artist” who enjoyed the challenges of constraints.

Final senior project presentation at Bowling Green State University. Photo courtesy of Imani Dixon.

Name a Black architect/artist who most influenced you as an emerging professional?

Paul Williams, one of the first Black licensed architects in the country, did so much great work in his lifetime, designing private homes for celebrities and public buildings, but there were also many barriers he had to face being a Black architect. Something that always sticks with me about his story was learning that he had to learn how to draw upside down to avoid making his white clients feel uncomfortable. That story makes me think about the built environment Black architects were designing in at the time, and how the designs inherently excluded us. I can imagine it was, and actually still can be, a difficult position to balance-- being part of a profession who has the power to impact people’s everyday lives, but being from a group of people who are rarely found in the same category.

Visiting Booker T. Washington’s home and Tuskegee University. Photo courtesy of Imani Dixon.

Name a favorite project completed by a Black Designer. Why is it your favorite?

I don’t actually have a specific project that is my favorite, but I’ve really enjoyed David Adjaye’s work since being introduced to it in architecture school. His designs don’t necessarily stick to a particular style but he does incorporate textures, materials, and patterns that artfully reference their historical or environmental context. The National Museum of African American History and Culture is one example and is a beautiful physical representation of Black contributions to American history and culture. I’m ashamed to say I haven’t actually been able to make the trip to see it yet, but absolutely plan to go see it as soon as I can.

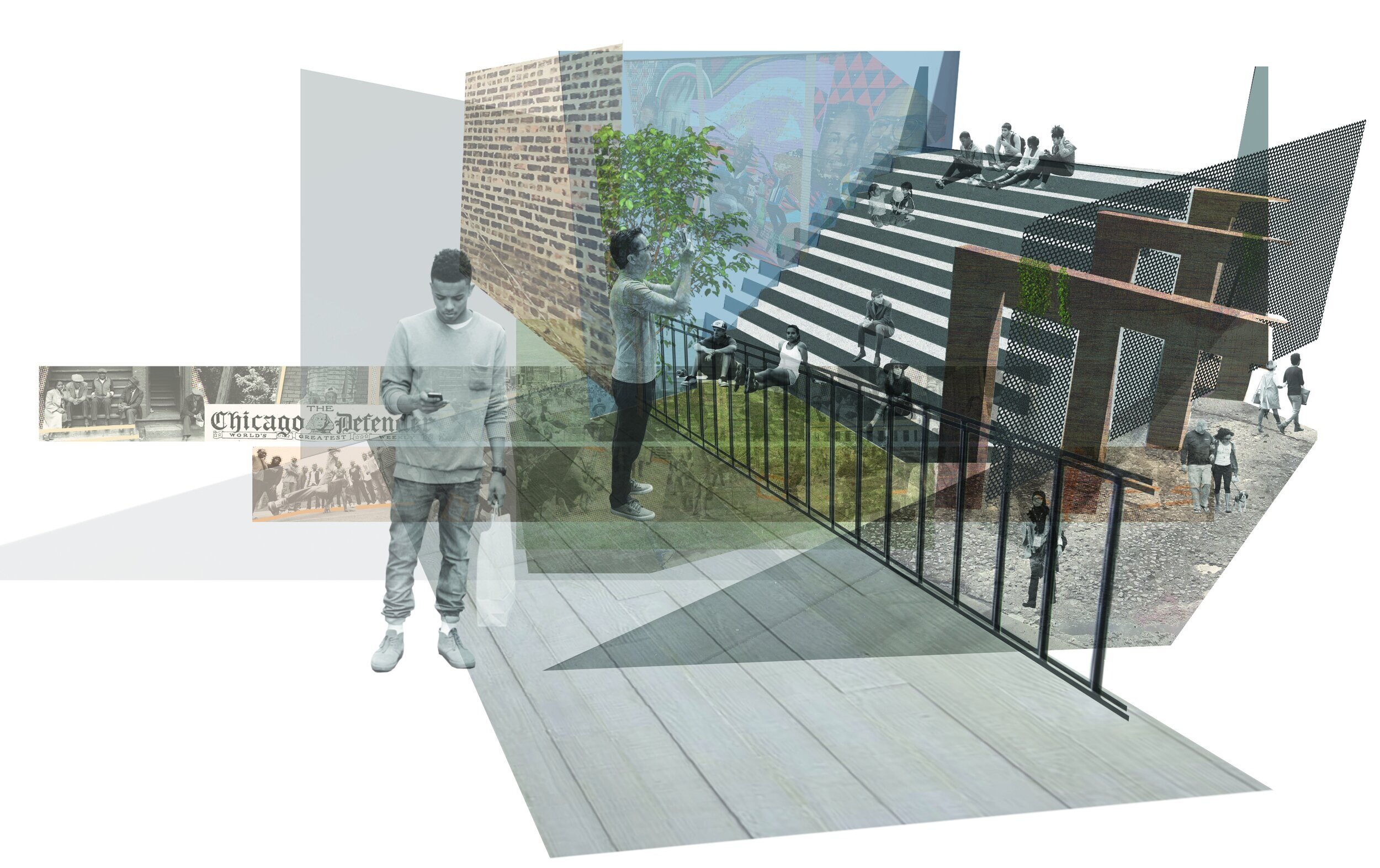

Graduate school thesis collage rendering, 2017. Photo courtesy of Imani Dixon.

How does your culture affect your studies and the way you design?

Although Black American culture is highly influential and embedded in overall American culture, I’m always aware that Black people historically haven’t had much influence in the design and planning of our own communities. The design of many American cities and their failures have actually been a catalyst for cultural eras in Black American culture, but I would love to see our creativity spark from positive environments now that there is more of a general consciousness around our issues. Being that we are so heavily influenced by our built environment, it is important to elevate design that impacts Black communities in a positive way while actively working to challenge and undo the injustices from housing and land use policies that we have been systemically faced with throughout history.

I believe the best thing I can do as a Black architect is to elevate my culture in the ways we work, memorialize, celebrate, socialize, and just live in the built environment. I strive to be visible, present, and available to people in my own community and uplift voices that are not traditionally given a platform. I also use the skills I’ve developed to dedicate my time to community-based initiatives while simultaneously mentoring young people interested in architecture who can, in turn, positively impact their own communities.

Graduate school thesis presentation at University of Cincinnati. Photo courtesy of Imani Dixon.

Are there any organizations that helped you grow in architecture? How did they help you grow?

When I was a third-year student at Bowling Green, I participated in a study abroad trip in Cayes Jacmel, Haiti, to help redesign a school that had been destroyed in the earthquake of 2010. This was in partnership with a non-profit organization called Social Tap, Inc. with The Haiti Initiative, so this is an organization that gave me one of the first experiences that shaped my ethos as an architect and catalyzed my interest in the intersection of architecture and social impact. The experience also helped me improve my non-verbal communication skills as a designer. Having a language barrier and presenting something to a client was not easy; I had to develop creative ways to present my ideas, visually and through other forms of communication.

The trip to Haiti also changed my perspective on sustainable design and sparked my interest in other Black cultures around the world. The reflection on my own identity led me to an idea for my thesis in grad school to analyze Black American identity in architecture and the built environment, called “Revealing Identity Through the Lens of Appropriation.” Even after having the opportunity to explore these topics, the lasting effects are still with me and even in the work I do now; I constantly interrogate how I can be more inclusive and thoughtful of the social impact in the work we do as architects-- especially in Chicago, a city with a deep history of racial segregation and socioeconomic disparities still present today.

Design presentation with the principal of Joie D’espoir Primary School in Cayes Jacmel, Haiti, 2013. Photo courtesy of Imani Dixon.

Tell us about I-NOMA. What inspired you to join NOMA?

Being one of the only Black people/people of color and always the only Black woman in my architecture classes, it was easy to feel alone and out of place most of the time. That experience paired with the traditional Eurocentric architecture curriculum also made it difficult to stay motivated, so I knew that I had to find others like me who found success in architecture as a career. I just Googled “Black architects” one day and that’s how I found out about NOMA. I didn’t have much success connecting with NOMA folks in Cincinnati at the time, but I knew I would have a better chance once I started my internship at Gensler Chicago in 2015. After getting there and asking around, I was introduced to the president of the Illinois Chapter of NOMA (I-NOMA) at the time, Jason Pugh, now the national NOMA president. I met a phenomenal group of people through I-NOMA and felt a sense of community in a very short time. I had such a great experience that I was 99% sure I was going to move to Chicago after graduation, and I did.

2019 NOMA Conference in Brooklyn, NY. Photo courtesy of Imani Dixon.

As a Design Manager and Mentor of I-NOMA’s Project Pipeline Design-Build, how are you guiding students to design their organization’s spaces? Tell us about the importance of ensuring the building users have a voice in making decisions regarding the spaces that they will use.

I-NOMA’s Design-Build program is part of the Project Pipeline initiative which provides support to aspiring architects from as young as elementary and middle school all the way to licensure. Design-Build is a program for late middle school/early high school students where we partner with a non-profit organization that serves youth and is in need of a redesign/reimagining of their space.

The first event before the actual Design-Build program starts with a ‘Design Charette’ where a meeting is scheduled with leaders of the organization, Design build mentors, and a few students to understand the organization’s goals for the partnership with I-NOMA. This is where they tell us how space currently functions, what works and doesn’t work, and what they need and want to get out of the redesign. The next few weeks of the program start off with the basics of architecture and construction process, such as what is expected in concept design to construction administration, since our students get to see the design completed in real-time. They also present to the client and learn to use the types of diagrams, drawings, and 3D modeling software architects use to portray design ideas.

2018 Design Build Grand Opening: Chicago Child Care Society. Photography by Cinesthetic. Photo courtesy of Imani Dixon.

Because the organizations are typically quite small, the meetings with the client typically include the end-users so they are engaged every step of the way. This is so important because those end users are the experts on what will make the space more functional and enjoyable to use every day. As designers and architects, we are providing solutions and translating those needs onto visual aids to communicate those ideas to contractors. I think that the students getting to understand that lesson is so important early on because they will eventually go to architecture school where they don’t necessarily have a client on their projects. This introduces them to that experience much earlier and the hope is that they will remember the feeling of positively impacting real individuals and communities they designed for.

Project Pipeline Summer Camp mentors at Willis Tower. Photography by Kai Brown. Photo courtesy of Imani Dixon.

If you were able to talk to your younger self, what would you say?

If I was able to talk to my younger self, I would tell myself to keep my confidence as I progress throughout academia and the profession. Being both a woman and Black at the same time, there were several instances, directly or indirectly, where I was told that this profession was not for me, or that my interests did not align with the status-quo of what architecture is supposed to encompass. Although I stayed focused, I have had to work to build my confidence back up after those experiences. Ultimately, none of those instances kept me from finding success in this profession and becoming a licensed architect, but I know that having more support from people in similar positions would have been helpful. I’m still early in my career so it’s only up from here!

Portfolio review at the University of Illinois, Chicago with NOMAS students. Photo courtesy of Imani Dixon.

What would you want to say to the next generation of aspiring Black women architects?

To the next generation of aspiring Black women architects, I would like to say continue being “you.” It may sound cliche, but there are so many ways we enter architecture school and begin to adjust ourselves, especially trying to fit into a profession that is not used to us and where we are typically the only one. Our creativity as Black women has been revealed in so many different forms-- our literature, our music, our dance, and even in our fashion, including the way we style our hair! It’s very easy to think of these skills as separate from the possibilities we can achieve as architects and designers but there can always be a connection. We see it done in so many other creative endeavors, so allowing ourselves to reference our culture and utilize our perspective can make us invaluable in the work we do.

Our collective experiences as Black women in architecture have allowed us to produce a strong network that isn’t limited by physical boundaries (thanks to social media and the internet), so never be afraid to put yourself out there. If you ever need someone to reach out to or even lend an ear, don’t hesitate to reach out to other Black women; many of us want to be that person that we may not have had or be able to pay it forward to another Black woman or girl who knows what it’s like to feel out of place.

ACE mentees after final presentation. Photo courtesy of Imani Dixon.